The music industry has changed drastically over recent years with its profits ebbing from the from the great heights in which they once stood. The music industry peaked in 1999 with an income of 28.6 billion US dollars, whilst 2016 only managed 16.1 billion dollars. Only in very recent years has the decline been subverted. The decline is widely believed to be result of the Internet. Introduction of peer to peer sharing networks such as Napster and the beginning of illegal torrent sharing provided the rest on which the bullet of dystopia was discharged. Regardless, the way in which we consume music in modern times is hugely different that of our not so distant past selves. As a result of which, the music industry has succumbed to a sudden metamorphosis. One which has reshaped the approach taken by all within.

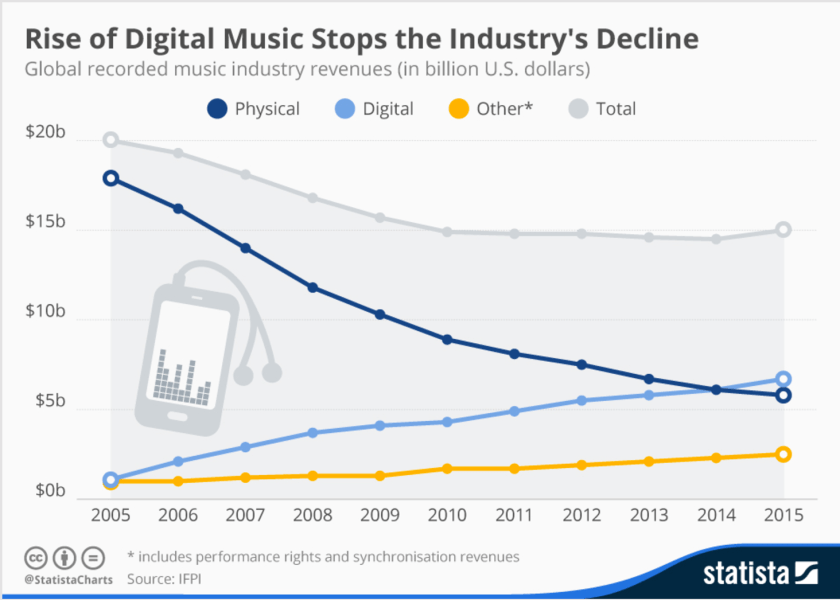

We as human beings lean towards that which is most convenient, a fact that industries have been exploiting have been since the conception of commercialised technology. Convenience sells. So why would the delivery format of music be any different? Since the introduction of vinyl to the gramophone, every technological innovation within the audience addressing department of music has been convenience inspired; until Apple released wireless earphones. Any how, this is a climb to which we seem to have reached a pinnacle, instant access to any recorded song at the tap of a finger, streamed directly at a satisfactory audio quality. All of these innovations are of course product of the competition within the media and technology driven society in which we exist. In modern times, it is safe to assume that the average music consumer no longer buys the majority of their music on physical formats. With physical sales making up only 34% of income in 2016. Digital formats first overtook their predecessor in 2014 according to Statista. The graph below depicts sales income from records sold between 2005 and 2015 and the first sign of improvement since the beginning of the decline. The term digital

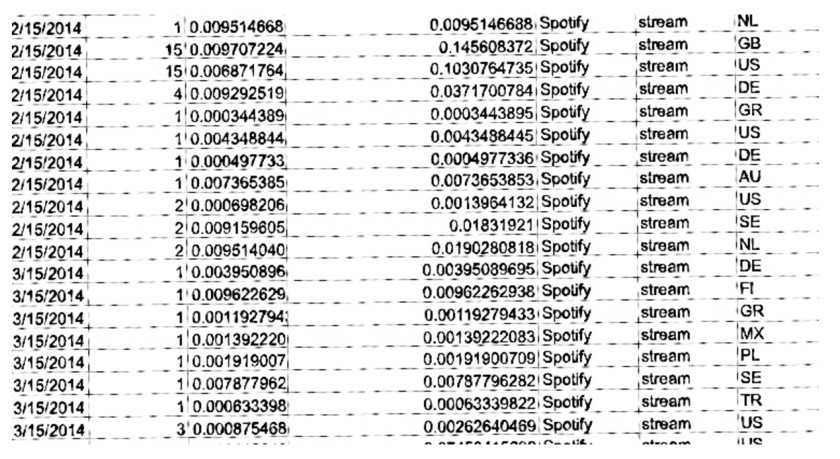

in this example is a blanket term applied to all types of digital format. This rise is product of the streaming revolution, the now predominant form of music consumption. Streaming is up on a worldwide scale by 60.4%. 100 million subscribers contributed an offset of 20.5% of all digital revenues in 2016, so one may assume that streaming is a wholly positive contribution to the industry. The financial times states “it looks as though the internet may resurrect the business it almost killed.” But then continues to suggest that only the higher tiers of the industry are currently benefitting. Spotify for example pays around £0.0048 per stream, a figure that cannot provide substantial enough return for smaller independent labels. Below is an excerpt of a Spotify pay receipt with streams amounting to 1,023,501. This amount of plays made an undivided income of $4,955.90. To see full payment receipt see: FULL RECEIPT AND ARTICLE.

However, the opposing argument of such a thought would be that in the modern age the production costs of music are at an all time low. An extreme example of this low production rate is an artist called Steve Lacy who produces music on his smartphone using Garageband and an iRig. An Artist whom has proceeded to work with big artists such as Kendrick Lamar. Along with this, the difficulty of self promotion has reduced with social media providing a convenient platform and business models such as fan funding creating possibilities for emerging artists, it appears the necessity of a gatekeeper lessens by the day. However the big money in streaming still relies on making your way on to featured playlists or other such big company promotion.

The recording sector isn’t the only department resisting turmoil. Whilst the live music sector is thriving financially (rising from 26.9 to 42.9 billion between 2015 and 2016), the figures are offset by the rise in ticket prices and by the increase of income in the large concert area. Of course the audience is growing also but this conglomerate mentality that consumes the music industry is having a heavy impact on the development of new talent and emerging artists. Large building development corporations are forcing good independent venues out of business. A good independent venue adds to the culture of its surroundings and helps the urban eco system. Providing a platform, or a stepping stone if you will to aspiring creatives, the small independent venue is key to the figurative ontogenesis of urban culture in the UK. The rise in demand for expensive inner city accommodation threatens these venues the most. Once the flats are inhabited, occupants tend to find the noise less than satisfactory, filing complaints, forcing closure and opening a door to prime real estate within a busy city centre, which may then be bought by a company very reminiscent of the first, who then convert to more flats. Seems like a fair system, right? According to The Guardian, The Point in Cardiff suffered this death: “The Point in Cardiff: they installed £68,000 worth of acoustic baffling to stop the complaints from a new development, and servicing the loan put them out of business. These little things just build up.” Many iconic venues have perished in recent years such as The Roadhouse is Manchester, Madame Jojo’s and The Astoria in London; not only down to corporation but other side effects of the modern world such as the increasingly high rent and overly punctilious licensing scrutiny. Many others such as the 100 Club and the Tunbridge Wells Forum are also considered to be at risk.

Many industry innovators are implementing new techniques to keep the market engaged. Such as the Biffy Clyro track released alongside the Samsung Virtual Reality advert campaign, with a VR experience music video. Other live performance bands such as Kasabian have also found a way to exploit this new technology, charging their audience to view a 360 VR live recording of their concert. This type of innovation increases the profit margins within the music industry, allows those who cannot attend live to enjoy the music and the gimmicky aspect engages the less active end of the viewer fanbase.

For the industry to thrive it must fall to the feet of its audience and asks that their appreciation for music is reflected in their contribution towards it and to the artists that create are made able to keep on doing so. This may seem a colossal task in the modern era when every occupant of western civilisation is over exposed to media, so there is very little point seen in appreciation, but schemes are underway that could provide the solution. Methods such as crowd funding are becoming ever more popular and could provide the necessary components to fuel future creation. Within the idea, the artists make request of their audience to fund projects. Companies Such as Indiegogo, Patreon and Kickstarter provide such a service. These are essentially forums in which the artists are able to make their request. The costs taken by the companies are mostly claimed to be running fees and tend to be a very small percentage, making it a stable platform for emerging talent.

Whilst the music industry on a whole is on a rise in the UK with profits “outperforming the UK economy over the past four years” according to ukmusic.org, the main question lies in sustainability and what is to happen in the future. With the creative petri dish of the small venue dwindling and the sentimentality and appreciation of the physical format inert, can streaming do enough to support the mammoth industry or will technological innovation take precedence once again? Fortunately music is one of those things pursued with a passion and love, and a song will always be sung, but the measures taken to ensure the industry survives must bow to the media immersed modern world and the audience that expects no exertion of effort.

http://www.ukmusic.org/research/measuring-music-2016/

http://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2016/05/26/band-1-million-spotify-streams-royalties/

https://www.ft.com/content/cd99b95e-d8ba-11e6-944b-e7eb37a6aa8e

http://diymusician.cdbaby.com/musician-tips/which-crowdfunding-platform-is-best-for-musicians/