There are many differences when mixing for Film when compared to the mixing of a song. These differences mainly arise in the desired application of the sound. For example, usually when we mix a song, we want to create a false but acceptable stereo image – the idea of a space. Now, this space can be anything we envisage that atmospherically corresponds with the recorded sounds. The way we achieve this is by recording sounds with ambient microphone techniques and applying effects such as EQ, compression and reverb in post production. But our approach must differ slightly when we approach mixing for film because our audience have a visual reference for the space and can therefore make subconscious judgements as to whether or not the audio sounds right within a space. The decision making process for the engineer should start by finding the ideal dynamic signature for each sound and progress to the ideal application of post-production effects both for the reality of a space and the desired effect of a sound.

To provide an overzealous example, if we had an instrument doused with a cathedral convoluted reverb in a song, as long as it works musically, dynamically and sonically alongside our other audio aspects, this is completely fine. However if we had a section of dialogue doused in the same reverb, but the visual reference for the space was a small concrete room, we would perceive this as unnatural, whether consciously or not we would know it’s not normal. This is all down to reference, the main tool of our sensory perception. I’m not saying that this would or has never be used, but it would feel unnatural and would therefore not be used to create a realistic nuance. Effectively mixing to visuals, creates another reference for glue – another medium to consider (the visual) and our decisions should be made accordingly. This is because of our brains natural tendency to reference patterns and correlations (our brain compares what we see and hear constantly so it know when something is amiss). This type of effect could however be used to connote an unnatural atmosphere. A great example of this type of processing is The Last Jedi episode of Star Wars in the telepathic scenes between Rey and Kylo Ren, the juxtaposed character archetypes of the film. Within the storyline, these characters have a telepathic bond, a fact which isn’t overtly stated until a fair way into the film. However, the audience are given this information by the audio. The two voices are placed within the same, ominous sounding space, telling our brain immediately that these two voices are communicating and exist within the same non-physical plane. In my opinion, this is a genius use of audio to foreshadow and develop a storyline.

Another attributing factor to the differences in mixing for film is the way in which it is consumed. Dynamic range and mixing in film is very much dependent on the audience. For example a large blockbuster film to be consumed in a cinema will be mixed so that the transient sounds are jarring and have a huge impact at around 100dB, the dialogue will be mixed so that it is loud enough to carry over the ambient sound of an audience (popcorn rattling, mumbled conversation and such) and will be compressed and mixed to sit at around 64dB relative to the audience. And the diegetic ambience of the film will sit just below. Music and score tend to sit somewhere between the highest transient sounds and the dialogue but should be applied subjectively depending on the desired effect. This is not necessarily so it is perceived as natural but because it provides the most immersive listening platform for the audience.

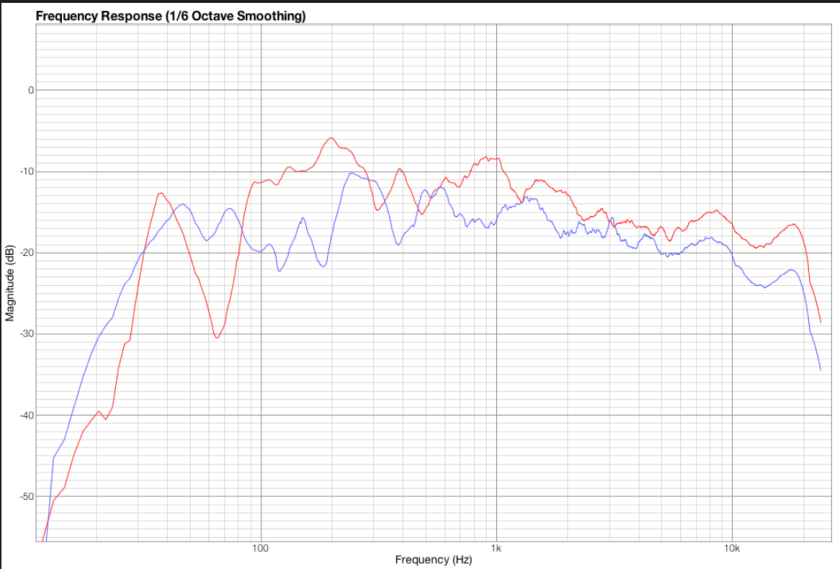

Once the audience has been considered, an engineer must also consider the listening environment. Using a cinema as the pinnacle and most dramatic of examples, one must consider the X-curve of a space. The SMPTE standard states that in the average cinema there will be a high roll off, algorithmically decreasing, attenuating the listeners perspective of frequencies between 2kHz to 20kHz because of the size of the space as well as it’s treatment. Cinema’s are designed to provide the most consistent listening platform possible. For example, the chairs are soft and plush not only for consumer comfort but because this makes the room sound more uniform regardless of its current capacity.

To achieve this it is important to know the system you are listening on and have solid points of reference for your audio level. An industry standard method for doing this is by running pink noise through the mixing system and calibrating all speakers to read at a universal volume from a single point (85dB is recommended). This is done with an external dB meter.

In conclusion, to create an effective mix for film one must not only consider the space we are creating within a film and the effect we wish this to have, but also the physical space in which our theoretical space is to be perceived. Then, to strike a critical, informed balance between all variables.